Zoroastrian Liturgical Ceremonies

| ||

|

Ceremonies & Liturgies

Liturgy Definition

A liturgy is a particular arrangement of prayers that priests use in the

performance of their duties, in service of the community, and in the

conduct of ceremonies conducted in a prescribed manner, setting and time

of day. The liturgy is often accompanied by a set of rituals. The

liturgy is also distinguished from the selection of Avestan verses

(mathras or manthras) used as daily prayers or when performing certain

tasks.

Types of Ceremonies

Zoroastrian ceremonies are primarily of two types:

ceremonies of the outer and inner circles. Ceremonies of the outer

circle are ceremonies that can be performed outside a temple and in some

cases by the laity. Ceremonies of the inner circle are ceremonies that

are always performed within a temple and more specifically inside the

pavi areas of the temple. Pavi areas are the consecrated inner sanctums

demarcated by a groove in the floor and areas where only ordained

priests may enter.

In addition, there are purification ceremonies conducted to purify or

cleanse a space or person in order to consecrate a space or prepare a

person to partake in a religious ceremony.

Ceremonies of the Outer Circle

These ceremonies may be performed outside the pavi area (inner sanctum)

of a fire temple. They are therefore either public ceremonies or

ceremonies performed in a home or public place. While, they are usually

conducted by priests, many can be led by competent lay persons.

The ceremonies performed in homes or public fires often require temporary fires as part of the ceremony. These fires are the Atash Dadgah - originally the court fire.

Ceremonies Using the Atash Dadgah

Ceremonies of the outer circle such as the Afringan and jashan

ceremonies employ the Atash Dadgah, a fire that is lit when required

and maintained for the duration of the ceremony. The Atash Dadgah is

consecrated with a recitation of the Atash Niyaesh as a prelude to the

ceremony.

|

| Priest lighting an Atash Dadgah |

The Atash Dadgah is maintained for the duration of the event on a round

metal plate placed on top of an urn. The urn is a scaled down replica of

the urns that hold the Atash Bahram or the Atash Adaran.

Some enterprising priests cover the plate with metal foil to make

clean-up after the event easier. Others cover the metal plate with a

thin layer of ash to simulate the ash that would have built up in an urn

with a continuously burning fire. If sandalwood is available, small

pieces of this wood, or a substitute, are placed over kindling shavings.

Next to the urn is an oil lamp called a devo. The priest uses the devo

to set the wood on the urn on fire - and to maintain the fire should it

go out during the ceremony. If the devo is constructed from a drinking

glass filled with oil on which floats a wick, it is called a

glass-na-devo. The attending priest lights the devo using a match. The

priest then lights a thin splinter of wood from the devo to ignite the

fire in the shavings on the urn. once the kindling shavings catch fire,

the kindling in turn sets the small pieces of wood on fire. A bed of hot

coals in the ashes, helps to maintain the fire.

|

| Priest tending to an Atash Dadgah |

Priests wear white as a symbol of cleanliness and light. They cover

their mouths to prevent their breath from reaching the flame. They also

sit on a white sheet spread on the floor.

on occasion, the priest ladles powdered incense on the fire. The ladle is called a chamach. The scent of the sandalwood fire and the incense fill the room and give it a traditional atmosphere.

After the ceremony, members of the congregation take turns to come up to

the fire, recite a line of prayer, and at times place a small piece of

wood on the fire to keep it burning. Some may place their fingers on the

rim of the urn and draw the energy of the fire up towards their chests

in a sweeping motion. Others may take a pinch of the ashes and rub it

once on to their foreheads with their thumb.

When the ceremony is finished, the fire is allowed to extinguish itself and the ashes are disposed.

Priests

|

|

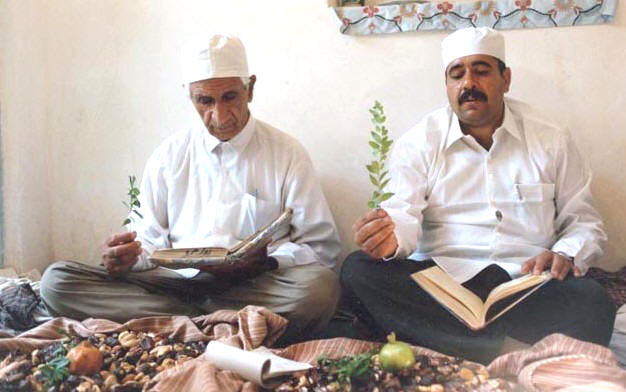

| Iranian Priests reciting the Afringan / Afrinameh while holding a sprig during a gahanbar in Yazd, Iran |

The Afringan ceremony described below

and seen in the photographs above and below, can be performed by one or

more priests or competent lay persons. If there are two priests

officiating, the senior officiator, is called the the Zaoti (or Zoti, cf. Zaotar). The second priest, called the Rathvi

(or Raspi), assists and tends to the fire. The ritual utensils and

items placed on the tray and sofreh represent the six elements of

nature. The priests represents the seventh element, humankind.

Priests with a background from India sit facing one another while

Iranian priests sit in a line often in the same line as the people

participating in the ceremony.

Setting and Sofreh

Customarily, all Zoroastrian religious ceremonies are conducted on a white linen sheet, called a sofreh,

spread on the floor. The sofreh represents the sacred space during the

ceremony. The sofreh is spread placed over a carpet that is placed in

the centre of the room, with chairs for the participants arranged around

the sofreh.

White is the symbol of cleanliness, purity, and goodness.

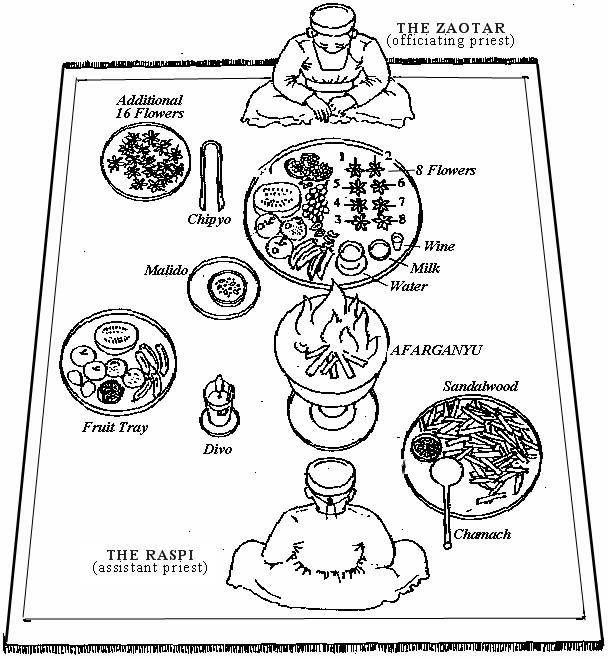

The utensils used in the ceremony are metal. The include the afarganyu or fire urn, a couple or more metal trays called a sace or ses, a chamach or ladle for placing wood and incense (loban) on the fire, and a chipyo or tongs used to move items.

|

|

| The setting for an Afringan ceremony (also the Jashan / Jashne) using the Atash Dadgah |

| Credit: Adapted from "Zoroastrianism: An Ethnic Perspective" by Khojeste Mistree as shown on Soli Bamji's site |

Symbolism

The jashan / jashne ceremonies of which the Afringan described below is a part, celebrate the coexistent duality of existence: the spiritual and material creations.

In the diagram and images above, the eight flowers can be seen arranged

in the tray or sace that is placed on the sofreh. The two rows represent

the spiritual existence, mainyu / mainyva , and gaetha / gaethya,

material or physical, existences (in later language: menog and getig).

The climactic moment of the ceremony is when the priests pick up and

exchange the flowers with the words "athe zamyat" symbolizing the

interchange or an interaction between the two realms of existence (for

an introduction to the two coexistent realms of existence, see our Overview page).

The exchange of flowers which are picked up from the top of one row

followed by flowers from the bottom of the other parallel row, also

symbolizes the transmigration of righteous souls, the united fravashis of the righteous between the two realms.

The seven aspects of creation and the corresponding Amesha Spentas (divine attributes) together with spenta mainyu, are represented in the setting and items used in the ceremony:

• The floor or ground represents the earth and the Amesha Spenta Armaiti;

• The fire represents the eternal flame, the spiritual fire, and the Amesha Spenta Asha;

• The priest represents human kind and Spenta Mainyu;

• Milk represents animal life and the Amesha Spenta Vohu Mano;

• The metal in the utensils represents the sky and the Amesha Spenta Khshathra;

• Water represents water, the environment and the Amesha Spenta Haurvatat;

• The flowers and fruit represent vegetation and the Amesha Spenta Amertat.

The ceremonial tray, the sace, represents as it were, the celestial

sphere and all aspects of creation including the spiritual and physical

realms.

White is the symbol of cleanliness, purity, and goodness.

Afringan Ceremony

The Afringan is a ceremony of blessing and remembrance. It is one of the

principal outer or public ceremonies in Zoroastrianism and is performed

during Gahambar / Gahanbar festivals and Jashan / Jashne ceremonies.

Afringan is also the name of the fire chalice used during the ceremony. The full ceremony consists of three sets of prayers:

1. Atash Nyaish and Doa-Nam Satayashne

The Atash Nyaish is a litany to the fire - prayers said when consecrating a fire used as part of a ceremony. The Doa-Nam Satayashne (or Stayishn) are words in praise of God in the Pahlavi language.

2. Dibache, Afringans and Afrins

Afringans are dedications to God, God's creation, divine attributes and angels.

|

| Afringan flower ceremony |

An Afringan ceremony is also called a flower ceremony as the

flowers placed in the sace are held up or, if two or more priests are

present, exchanged between the priests during recitation of that part of

the Afringan's humatanam prayer (Y35.2). In Iran, when plants are not

available, a finger is sometimes held up instead. There the prayers that

accompany the holding of the sprigs are called the Afrinameh. Priests from India generally use flowers - at times roses. Priests from Iran generally use myrtle (murd), pomegranate or jujube (red date, or Chinese date) sprigs. The length of the flower or sprig should be a hand span in length.

According to Manekji Hataria's (1813-1890 CE) article on the Religious Ritual Practices of the Iranian Zoroastrians in Zoroastrian Rituals in Context

by Michael Stausberg (see link below), the myrtle sprig is dipped in a

vessel called 'nava' containing water. "When starting a new karda

(section), at the word afrinami / afrinameh, the priest and everyone

present picks up a leaf or flower and raises a finger of her or his

right hand. Then while reciting upto vispo khatrhem they raise the

second finger." The fingers are lowered when reciting the Yatha Ahu

Variyo prayer. This process is repeated for every karda.

|

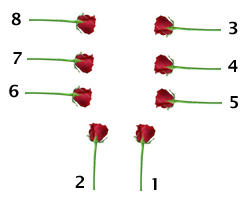

| Flower Order |

In a full fledged ceremony, eight plants / flowers are used. The eight

flowers are arranged in one quadrant of the sace in two parallel rows of

three flowers each with the remaining two flowers placed at the end of

each row and facing each row. The symbolism is explained above.

The Persian Rivayats state that five (symbolizing the five periods or

gahs of the day) sprigs / flowers are be used except "when one Dahman is

recited", in which case three sprigs / flowers are used.

The choice of Afringan prayers depends of the occasion and often contain a Pazend or Persian portion called a dibache

or a preface to the Avestan prayers and a remembrance of the souls of

the departed, including great kings of Zoroastrian history, heroes,

priests and deceased members of the family sponsoring the Jashan. The

dibache is recited in a soft tone. The dibache is recited softly. The

Afrin are Pazand prayers of blessing where the priest or person saying

the prayers seeks to spread the spiritual strength of the ceremony to

all present.

The Afringan ceremony is explained further in avesta.org's page

on the subject. After the flower ceremony, the priest touches the

different metal vessels with his metal fire-tongs in the four directions

of the compass and then again in the directions in-between the four

compass points.

3. Doa Tandorosti

These Pazand prayers

are the culmination of the prayer ceremony. The first two steps enable

blessings of strength, health, and well-being to be extended to all

present, and indeed all of humankind as well as the souls of the

departed. If the occasion honours particular individuals, their names

are mentioned in the benediction. In Persian, tan means body and dorost

means correct or healthy in this case.

At the end the prayers, the priest may asks the gathering to stand, hold

hands and join in prayer. This is an act of solidarity and community.

The prayers are usually two ahunavars, and one Ashem Vohu. A fravarane

is sometimes added.

Baj Ceremony

Baj ceremonies are prayers said before undertaking a task. They are also prayers said for the dead on the occasion of a death anniversary. The baj can be recited before eating or drinking when it can be compared to grace said by Christians.

Dron Ceremony

The Dron (Pahlavi: yasht-i drôn. Avestan: draonah) is the Baj ceremony

conducted by priests that blesses and gives thanks for food in a

prescribed ritual. Dron is both the name of the ceremony and the

palm-sized unleavened ritual bread made for the ceremony. The ceremony

takes about fifteen minutes to complete and can be conducted by both

priest and laity.

The ceremony requires the recitation of chapters 3 to 8 of the book of Yasna.

Ceremonies of the Inner Circle

The Yasna, Visperad, and Vendidad (Videvdat) ceremonies are ceremonies of the inner circle and can only be performed within the pavi area (inner sanctum) of a fire temple.

Yasna Ceremony

The Yasna ceremony is the highest of the inner circle ceremonies and requires the recitation of chapters 1 to 72 of the book of Yasna. The purpose of the Yasna ceremony is to purify the world, strengthen the bond between the spiritual and physical existences, and to promote good health. As with all ceremonies of the inner circle, it is performed in the pavi area (inner sanctum) of a fire temple.

|

Yasna Meaning

Yasna is commonly taken to mean worship or dedication as well as being

related to the words yaz, yezi (Avestan) and later yazishn (Middle

Persian), words that evolved yet later into ijeshne and then Jashn / Jashne / Jashan.

Given the association of yasna with jashne, a thanksgiving festival,

yasna could very well carry a meaning similar to celebration such as

honouring or venerating.

In addition, the Avestan yaz is identified with the Sanskrit root word yaj which has been taken to mean worship or to praise. L. H. Mills in his The Zend Avesta: The Sacred Books of the East, Part Thirty-one, Yasna II, page 203, says that the word yas means 'desire to approach' or 'desire the approach of'.

Yazishn-Khana / Gah

A yazishn-khana or yazishn-gah, the room or place for the yazishn, is noted in the Middle Persian Persian Rivayats as being part of a Dar-e Mehr, a neighbourhood place of worship, and separate from the atash-khana or atash-gah or , the room or place for the fire.

Time or Gah / Geh of the Ceremony

The stipulated time for the entire ceremony is during the morning watch or Hawan gah / geh (In the Avestan languages, Havani ratu, and also known as Havan-ni-Meher cf. Havan-e Mehr). [Also see our 365-day calendar grid and the section on Divisions of the Day in our calendar pages.] During the first seven months of the Zoroastrian calendar, that is, the Rapithwan above ground months, the Havan gah is the period of the day between sunrise (when the rays of the rising sun have dispelled the darkness of the night) to noon. For the last five, cool, Rapithwan below ground months of the Zoroastrian year, the Havan gah extends from sunrise to 3 pm.

|

| Novice learning the Yasna ceremony |

Preparatory Activities

Prior to the start of the Yasna ceremony, a priest (often the Rathvi /

Raspi who will assist the senior Zaoti / Zoti priest) will assemble the

materials required for the ceremony including the plants that play a

central role in the rites. Some traditional temples have a well and

plants such as date palms and pomegranate trees growing within the

premises.

In those temple grounds that contain growing date palms and pomegranate

(Av. hadanaepata) trees, the priest walks to a date palm with a pot of

consecrated water from the well and a sharp knife. After selecting a

suitable leaf, the priest washes his hand and carefully cuts the leaf

while reciting a manthra. After cutting the leaf, the priest washes the

leaf and his hands, and enters the Yasna-gah (see below),

the Yasna place, within the temple with the leaf. There he cuts the

leaf into three strips and braids the strips into a cord which he uses

to ties the baresma (barsom)

bundle symbolizing the unity and synergy of the plant world. The ritual

collection is repeated for a cutting of a pomegranate twig.

In addition to the pomegranate twigs, pomegranate leaves, date palm

strips and consecrated water, sprigs of the ephedra twigs as well as

milk (cow's milk in Iran and goat's milk in India) will be used in the

preparation of the haoma (hom) extracts (also see ab-zohr below).

Ab-Zohr

The central rite of the Yasna ceremony is the ab-zohr - the preparation of a liquid extract that is part of the haoma or hom family of healing methods. Ab-zohr means strength-water in Persian, a name that is derived from the Avestan ape-zaothra. The Parsi (Indian Zoroastrian) name for the rite is jor-melavi from the Gujarati, jor / djor meaning 'strength' and melavi meaning 'introduction'.

During this rite, two liquid preparations called parahom (from para-haoma) and hom (from haoma)

are prepared during different phases of the Yasna ceremony: the first

being the Parayagna or Paragna - the pre-yasna phase, and the second

being during the yasna ceremony itself. The first preparation is

consumed by the senior Zoti priest while a part of the second

preparation is poured into the temple's well or a nearby stream in a

culmination of the ab-zohr rite. Prof. Mary Boyce translates zaothra as

libation - a libation being a liquid that is poured out during a

religious ceremony. The remainder of the second extract is consumed by

the temple's priests and some of the laity.

Haoma

or hom is also the name given to the principle plant, ephedra, used to

prepare the parahom and hom extracts. It is also the name given to the

entire family of health-giving and healing plants used in conjunction

with the ephedra as well as their extracts.

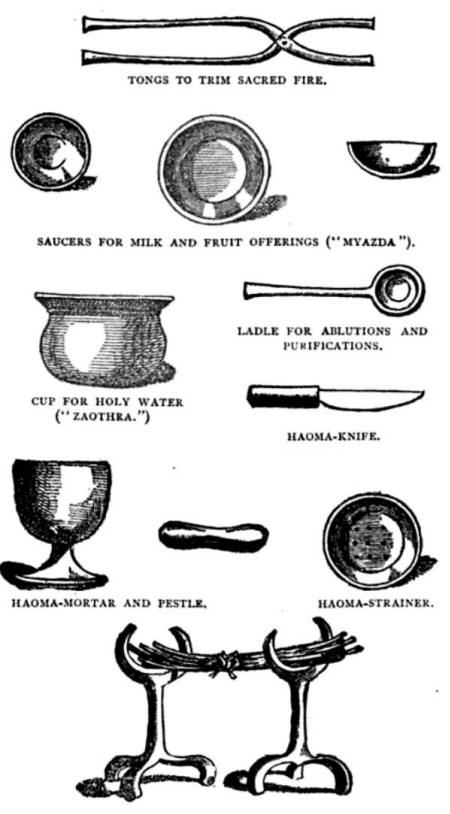

Parahom Preparation Implements / Alat

|

| A selection of priestly ceremonial utensils - alat |

|

| The different priestly ceremonial items - the alat |

The ritual implements used to produce the hom preparation are part of

the priest's ritual implements or alat. They are the mortar (hawan) and

pestle (dastag/abar-hawan/labo) for pounding and extracting the juice

from the plant, a nine-holed strainer (surakhdar tasjta), and a bowl for

holding the parahom.

A priest who knows how to prepare various kinds of haoma extracts and their benefit, is called a hawanan.

The ritual preparation of parahom & hom is described in Mary Boyce's article: Haoma Ritual at CAIS.

Pre-Yasna Ceremony

Parayagna / Paragna

The prelude to the central rite of the Yasna ceremony is the parayagna (or paragna), meaning before-yasna (para is Avestan for before and yagna is the Vedic Sanskrit equivalent, cf. yajna, to yasna.). During the parayagna, the ceremonial utensils called the alat and other items used in the Yasna ceremony are consecrated and the plant twigs whose juice will be extracted are cleaned by a ritual washing and assembled. The twigs include the barsom twigs (now often replaced by wire strands), other related plants (urvaram, for instance pomegranate twigs and leaves) and the aiwiyaonghan / aiwyaonghana, date palm twigs. The barsom symbolizes the channel through which the material creation gaetha / gaethya connects with the spiritual realm mainyu / mainyva (in later language: menog and getig).

Preparation of Parahom Extract During the Parayagna / Paragna Ceremony

The first parahaoma extract is prepared - usually by the Rathvi / Raspi

priest - as part of a preliminary or preparatory rite to sanctify the

worship and preparation area immediately prior to the main Yasna

service. The materials that are to be pound together for the first

parahom preparation - three small ephedra twigs (sometimes dried), one

pomegranate twigs, some pomegranate leaves and water - are readied. The

Raspi cuts the twigs and leaves (into pieces small enough that they will

fit into the mortar) while reciting Yasna 25.

Then the chopped twigs, leaves and a little consecrated water are

repeatedly pounded together during a recitation of Yasna 27. The liquid

ground mixture is poured onto the nine-holed strainer and the strained

liquid is collected below in a designated bowl. The Raspi collects the

twig and leaf residue from the strainer and places the residue close to

the fire so that it may dry completely before the end of the ceremony.

Preparation of the Hom Extract During the Yasna Ceremony

After the preparation of the parahom, the Rathvi / Raspi is joined by

the senior Zaoti / Zoti priest. Following the joining formalities, the

Zoti starts reciting the opening Yasnas including Yasnas 3 to 8, the

Sarosh Dron, and Yasnas 9 to 11, the Hom Yasht. At Yasna 11.8, the Raspi

pours a few drops of the parahom from one of the containers onto the

barsom bundle and hands the remainder to the Zoti. At Yasna 11.10, the

Zoti consumes the parahom prepared by the Raspi in three sips.

The Zoti begins to pound the twigs for the second hom preparation

between Yasna 22 and 28. While the first preparation had been made using

water, milk (cow's milk in Iran and goat's milk in India) is used for

the second pressing. The second mixture brings together the beneficial

properties of plant life, water and animal milk in order to best promote

physical health and healing. Preparing the hom extract during a ritual

recitation of the Yasna, enables the mixture to promote spiritual health

as well.

The pounding is suspended during Yasnas 29 and 30 and resumed when

during Yasnas 31 and 32, the Zoti pounds the mixture three times,

straining some of the liquid into one of the bowls after each pounding,

each time returning any crushed residue to the mortar. During Yasna 33,

the Zoti pours the last of the mortar's contents over the strainer and

squeezes the fibrous residue so that it yields its last drops. He

removes the fibrous residue from the strainer and places it on a

designated spot beside him on the floor. The Raspi picks up the residue

and places it beside the fire next to the previous residue from the

parahom preparation (in order that this batch may also dry completely).

During recital of Yasna 34, the now empty mortar is inverted and the

milk-dish is placed the mortar's upturned base. The bowl containing all

the squeezed hom extract is set of the top of the milk-dish in a

three-tiered arrangement.

The recitation of the Yasnas continues and at Yasna 62, the Raspi feeds

the now dried ephedra and pomegranate fibrous residue to the fire.

During the recitation of the remaining Yasnas, the Zoti removes the hom

extract container from the top of the three-tiered arrangement and

re-rights the upturned mortar. He then pours the extract between two

bowls and the mortar thoroughly mixing all the extract and milk, and

finishes with all three containing the same amount of of the hom

mixture. After the recitation of the final Yasna, 72, both priests carry

the hom mixture in the mortar to the temple's well (or a nearby stream)

and make a libation by pouring small amounts three times into the well

or stream. Small quantities of the remaining hom mixture are consumed by

the temple priests and the remainder is available for special needs of

the laity such as thanksgiving for a newborn child or administering the

last rites to a dying individual. Any remaining hom juice is poured over

the roots of trees, especially fruit trees.

Visperad Ceremony

The Visperad ceremony requires the recitation of chapters 1 to 72 of the

book of Yasna, and chapters 1 to 24 of the book of Visperad. The

chapters are combined or substituted one for another according to a

formula based on the day and month of the year called the sih rochak, the thirty days.

The Visperad is recited as part of the liturgy used to solemnize

Gahambars (seasonal gatherings and feasts) and Nowruz (New Year's Day).

The Visperad is always recited with the Yasna.

Vendidad Ceremony

The Vendidad ceremony requires the recitation of chapters 1 to 72 of the

book of Yasna, chapters 1 to 24 of the book of Visperad and chapters 1

to 22 of the Vendidad. As with the Visperad ceremony, the chapters are

combined or substituted one for another according to the sih rochak

formula.

Because of its length and complexity, the Vendidad portions are frequent read rather than recited from memory.

When the Vendidad is recited on its own and not accompanied with a ritual, the ceremony is known as the Vendidad Sadé.

The Vendidad ceremony is to be performed between nightfall and dawn.

External links:

» Afringan Ceremony at avesta.org

» Soli Bamji's site

» Zoroastrian Rituals in Context by Michael Stausberg

» The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran: Their Cults, Customs, Magic Legends, and Folklore by E. S. Drower, Jorunn Jacobsen Buckley